A Summer Job in Tramore

Staff at Tramore Amusement Park in 1931.

They were looking for a porter down in The Atlantic Hotel. It was mid-January, time to be getting your name in if you wanted a job for the summer holidays. I was 14 and most of my schoolmates had jobs lined up; in Freddie’s and in Dooley’s, as kitchen porters in The Majestic, or trainee barmen in The Hibernian.

my father said, as he sat at the head of the kitchen table in his navy bib and brace having his tea. my mother added, bending to take an apple tart from the oven. Our dog Sean, a stray who wandered in off the streets one day and never left, looked up from his basket beside the fire, and for a moment I thought that he was about to add his tuppence worth, but he just yawned and went back to sleep.

The Atlantic Hotel, sitting on a gentle slope overlooking Railway Square, was closed for the winter, cold and gloomy looking in the gathering dusk. Somebody said that the owner lived in a big house in Riverstown. Off down the Prom with me, the tide roaring in the background. The house in Riverstown was in darkness but when I pressed the bell the porch light came on, bathing me in a square of bright light. A grey-haired middle-aged man in an open-necked shirt, navy cardigan, corduroy pants and slippers opened the door and looked me up and down. he said. I answered, wondering if he was mad. he replied crossly, leading me into a large, bright sitting room where three children sat around a table doing their homework. They looked up at me for a moment before returning to their books. This was a posh room, far different to the rooms in our small house in Market Street.

I almost sank to my knees in the thick white carpet. A huge gilt-edged mirror, flanked on both sides by oil paintings, hung above a blazing coal fire, the dancing flames of which were reflected in the glass doors of a highly polished mahogany sideboard containing silverware, Waterford Crystal, and a China tea service. Sensing my discomfort in such plush surroundings, the man motioned me to a large armchair beside the fire. I decided that if he mentioned those boots again that I would make a run for it, but he patiently explained that “a boots” was another term for a porter and that one of my duties, should I secure the job, would involve polishing the boots of overnight guests in the hotel. My working day, he continued, would be a long one, from seven in the morning to seven in the evening, six days a week, and the work would include carrying suitcases, cleaning, and other duties. He concluded by saying that in order to secure the job I would have to get two references; one from the Parish Priest and the other from the Superior of the Christian Brothers School. The interview at an end he thanked me for my time and showed me to the door. As I walked away, the porch light went off, leaving me to face the Prom in darkness.

My father almost choked on his tea the following day when I told him about the references I would need for the job. he spluttered.

my mother added, leaning across the table to refill my father’s tea cup. Our dog Sean looked up from his basket beside the fire and seemed to nod in agreement. Looking back over a span of more than 60 years, I now realise that my father, simple, honest working that he was, looked upon the need for references as a reflection on our honesty as a family. Sure, I would have to work long hours, but no more than he ever had to work to rear five of us, and it would keep me off the streets and put a few bob in my pocket as my mother said, but the fact that I was a son of his should be reference enough.

The telephone box in Post Office Lane was empty for a change. Through its small windows I could see the Rex lit up like a ship in the night. The poster said that Pete Kelly’s Blues, a story of the Roaring Twenties, was showing that night. I’d love to see that, I thought to myself, as a voice on the other end of the line shouted, Press button A you eejit, I said to myself, as the coins tumbled into the box. As I replaced the telephone I wondered if my father would give me the money to go and see Pete Kelly’s Blues.

A sunny Sunday afternoon in early summer and still no sign of a job for the school holidays. My father and I go down around the amusements. Crowds pour off the buses into Railway Square, wide-eyed children clutching small buckets and shovels run ahead of their parents, eager to be first on the beach. Somebody laments the recent closure of the Waterford to Tramore Railway Line. Billy Bible passes us on his way to The Rex. Lar Keoghan sits on a beer crate at The Seaview Hotel playing on his accordion, the ash dangling precariously from the top of his Gold Flake cigarette.

In the shooting range nearby a line of air guns rest on the counter, their highly polished stocks glinting in the afternoon sun. A well-known Tramore character called Limerick Bill is sitting on a seat outside the shelter, knitting a jumper. As Johnny Cash sings a fellow in a kiss-me-quick hat punches the living daylights out of a leather ball hanging from a chain outside The Strand Amusements.

The crowds are three deep around The Spinner, where Gerry Dalton sells tickets for prizes, which include a statue of The Infant Child of Prague and portraits of The Sacred Heart and John F. Kennedy. God be with the days.

Brendan O’Brien and The Dixies unload musical equipment from the back of a van outside The Atlantic Ballroom. Joe Mac shouts a greeting to somebody across the road. In Piper’s Field old Johnny Piper leans on the half door to his caravan and watches his daughter Daisy guide a swinging boat in to land.

My father stops to light his pipe outside McCoy’s Fish and Chip Shop and we spot a sign in the window which says: STRONG BOY WANTED FOR YARD WORK. he says, pointing the stem of the pipe towards the sign.

McCoy’s stands cheek by jowl with The Atlantic Ballroom, an old fashioned fish and chip shop with wooden chairs and tables and sawdust on the floor. They do a roaring trade all summer long. Sometimes late at night a row breaks out, tables are overturned and salt cellars roll across the floor. The guards are sent for, order is restored, and it’s business as usual.

Mr McCoy, a huge man with a shaven head, stands beside the cash register with a cigarette hanging from the corner of his mouth. His wife stands with her back to him, tossing chips in a basket above an oven of sizzling fat. Tired looking girls from Waterford keep her topped up with buckets of chipped potatoes, ducking in and out of a back room like ghosts in a cloud of steam. my father says, looking down at me and winking. We move on.

I spent the rest of that summer, and many other summers of my boyhood, working as an assistant to Mary Armstrong in the Pitch and Putt Club halfway down the Prom. Mary was a colourful character, known and loved by locals and tourists alike.

For years she worked in a small picturesque kiosk overlooking two splendid pitch and putt courses and a putting green, which was as smooth as a billiard table.

Mary had a great rapport with all her customers, particularly the showband stars of the era who regularly played on the course and always left their calling cards; small coloured postcards of the showband, which took pride of place on the walls of the kiosk.

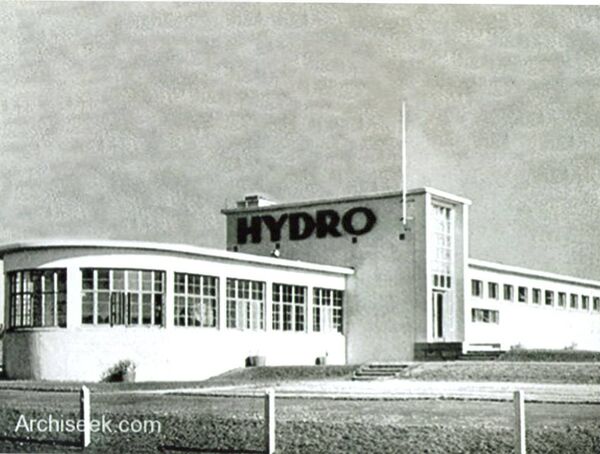

Today, this whole area is a sorry-looking sight. The pitch and putt courses and the colourful kiosk are long gone, replaced by a car park. That mighty building, The Hydro, and the ornamental fountain in front of it have been demolished and weeds grow wildly in what was once the putting green.

But, thankfully, due to its magnificent beach and other bathing spots, like the Guillamene and Newtown Cove, Tramore remains one of the most popular tourist destinations in the South East.