‘The sea has no mercy on dreamers…’

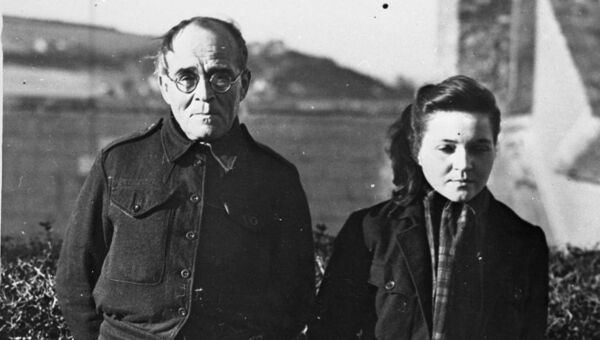

The Müllers in Helvick, Co Waterford, January 1950. Photo: Courtesy Waterford County Museum

At 5pm on Saturday, January 7, 1950, Helvick Head RNLI Station was informed that a 16-foot sailing boat carrying Germans Paul Müller (aged 63) and his daughter, Aga (aged 18), had left from Kilmore Quay at 11am that morning.

At 2pm, the boat had been sighted off the Hook Tower. Subsequently, at 4pm, it was reported off Brownstown Head. After that it was lost sight of.

Around this time, a strong wind began to rise. As darkness fell, it reached gale force.

As morning approached, all hope of finding the Müllers’ boat began to fade.

On Sunday afternoon, PJ Morrissey (Honorary Secretary, Helvick Head RNLI), while searching the coastline accompanied by Thomas McGrath, sighted the boat drifting dangerously near the rocks off Ballinacourty Lighthouse. Morrissey at once telephoned Helvick Head. The lifeboat ‘Agnes Cross’ was put to sea without delay. Enduring difficult conditions, the small yacht called the was found on the shore.

The second coxswain and another volunteer boarded the yacht. The exhausted man and girl had anchored the previous afternoon, but the cable had parted. The was towed to Helvick Pier and the lifeboat was back at her station at 4.30pm.

An exhausted Paul Müller and his daughter received a warm and hospitable reception. This happened to be the ninth occasion that the Müllers had been rescued since they had left Berlin in August 1949.

Arriving in Ireland on New Year’s Day 1950, the Müllers already had quite a reputation for their misadventures, appearing in newspapers across the world. From October to January, they needed to be towed or rescued on several occasions along the British coast. The Müllers spent Christmas Day in Milford Haven, having a festive dinner with the local vicar and his wife.

The Müller family, like many Berliners after the war, not only suffered destitution but were separated by the division of the German capital. Paul and Aga found themselves in the repressive Soviet Russian sector, while Paul’s wife and son, Horst, lived in the American sector of the city. Determined to attain a better life and re-unite the family in Argentina, father and daughter decided to covertly build a boat and slip down a small waterway that ran close to their home.

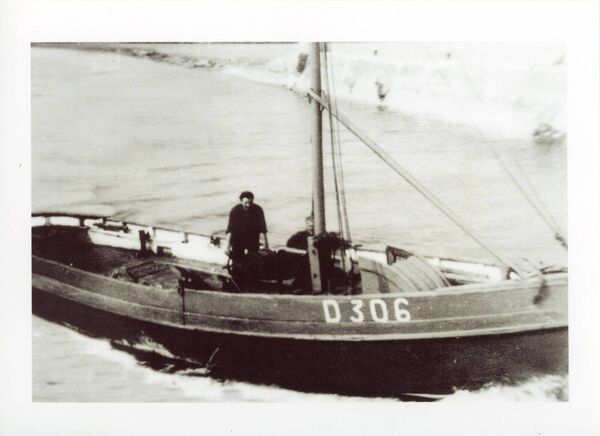

The originally belonged to the Kriegsmarine. Müller added extra planking to withstand Atlantic storms, as well as a keel, a mast and a cabin with water tanks and buoyancy.

When leaving German waters, they were chased by a surveillance boat before reaching Dutch waters. Previously, Paul had crossed the Atlantic single-handedly in the late 1920s. Converting an 18-foot fishing boat to sail, Müller reached close to Charleston, South Carolina. Paul later married his childhood sweetheart in New York before returning to Germany.

New Year’s Day 1950 saw Kilmore Quay spring into the national headlines with the unexpected arrival of the Müllers. Around 11am, some fishermen noticed a small boat in distress on St Patrick’s Bridge, a dangerous reef east of the harbour. Mark Bates mustered a crew and set off in his fishing boat, . Skipper Bates saw two people on the distressed boat in oilskins, waving for aid. They were pulled free and towed into harbour. It was reported that their faces were caked with dried salt, as the pair staggered ashore.

While in Kilmore, the Müllers were offered free accommodation for the winter months before continuing their voyage in more favourable conditions in spring. The offer was declined, as Paul and Aga insisted on continuing their journey. Despite poor weather, they set sail on Saturday morning, January 7.

From Helvick, the Müllers made their way to Cork Harbour, looking to have their boat overhauled at Crosshaven. From there, Paul and Aga’s next destination was to be the Canary Islands. A newspaper reported that the Müllers had reached Ardmore, Co Waterford, on January 11, having taken them over 24 hours to sail only 10 miles, due to a strong wind.

It was subsequently noted that they were towed into Ballycotton, Co. Cork, having made little progress. Leaving Ballycotton on January 16, it was reported that an offshore breeze obliged them to stand well out to sea. It was long after dark when they reached Cork Harbour, a distance of 10 miles.

The reported that the Müllers had left on Valentine’s Day for the next leg of their journey to the Canary Islands. Paul estimated the voyage would take them about three weeks and that they were sufficiently stocked with provisions. Both father (who had celebrated his 64th birthday while in Cork) and daughter were said to have been in good spirits.

In July 1950, news came of the tragic final episode of Paul Müller’s story. The Müllers left Freetown, in Sierra Leone, on June 14. 13 days later, Paul took ill. On July 2, they dropped anchor on the coast of Liberia. As Paul lay tossing below deck in his death throes, raiders in canoes took advantage of the perilous situation, seizing the Müllers’ reserves. Fearing their return, Aga cut the heavy anchor (presented to them in Helvick), turning the boat seawards. Paul died during the night. Aga managed to get ashore. She traversed treacherous country in bare feet for six hours before reaching a township called Buchanan. Paul Müller was buried in a Liberian grave by two Irish Missionaries. It was a sad end for a man who only dreamt of a better life for his family. As the late Dungarvan historian, John Young, wrote, “The sea has no mercy on dreamers.”

In August, Aga was flown to Dublin. Courted by the printed media, she decided to only speak to the . The Dublin paper published a successful series of interviews detailing her experiences. Later, Aga joined the newspaper staff, marrying a fellow journalist in the . Aga Cantwell (née Müller) died peacefully on December 19, 2022, in the loving care of the staff of Leopardstown Park Hospital, Dublin.